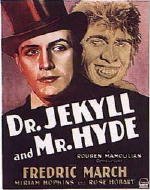

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1931)

The first horror film I ever saw was Victor Fleming's 1941 Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde with Spencer Tracy. I was eight years old. I pleaded with my dad to let me watch it, and to my surprise he did. And there began my obsession with that film and with the horror genre.

The first horror film I ever saw was Victor Fleming's 1941 Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde with Spencer Tracy. I was eight years old. I pleaded with my dad to let me watch it, and to my surprise he did. And there began my obsession with that film and with the horror genre.So it has always been with a sense of loyalty to the 1941 film that I have approached the earlier, and more critically successful, film by Rouben Mamoulian. It is not hard to see why this has fared better with the critics: It's far more thematically complex than the '41 version, whose sub-Freudian nonsense got in the way of what was really just a jolly good yarn in Hollywood's best style. This '31 film probes deeper into the Jekyll-Hyde myth, exploring God, evil and the human condition on a fairly epic scale.

Universal's Dracula and Frankenstein, both released earlier the same year, went straight into the horror action - all graveyards and bats and eerie lighting. Not so with Jekyll, made by Paramount. It doesn't feel like a horror film in the same sense at all, and there is little in the first reel to suggest any horror. We're on quite different territory.

Universal's Dracula and Frankenstein, both released earlier the same year, went straight into the horror action - all graveyards and bats and eerie lighting. Not so with Jekyll, made by Paramount. It doesn't feel like a horror film in the same sense at all, and there is little in the first reel to suggest any horror. We're on quite different territory.The movie starts as it means to go on - by placing us firmly in Jekyll's shoes. The battle between good and evil we are about to watch is not happening in some other place, with some other person, but in us. We are Jekyll and Hyde. I confess to finding the prolonged point-of-view sequence a little laboured, but once it's out of the way, Mamoulian's approach is altogether more subtle.

From now on, the film will be constantly implicating everyone in the picture - and the audience - in the fate of Jekyll. Mamoulian does this by frequently matching shots between scenes, by juxtaposing and layering images in order to create an association, by using split-screen to suggest identification between characters, and by shooting from Jekyll and Hyde's points-of-view.

For example, early on in the film, Jekyll (Fredric March) is caught kissing a dancing girl (Miriam Hopkins), to whom he has attended after an assault. It's an incredibly sexual scene for its era, and we are left with a shot of her naked leg dangling suggestively. This then dissolves into the next shot of Jekyll and Lanyon (Holmes Herbert), but the two images are layered for a few seconds, thus associating Lanyon also with sexual desire. Lanyon is later to reprimand Jekyll for his behaviour, but Jekyll's response is to charge Lanyon with having the same desires inside him - as the earlier shot suggested.

For example, early on in the film, Jekyll (Fredric March) is caught kissing a dancing girl (Miriam Hopkins), to whom he has attended after an assault. It's an incredibly sexual scene for its era, and we are left with a shot of her naked leg dangling suggestively. This then dissolves into the next shot of Jekyll and Lanyon (Holmes Herbert), but the two images are layered for a few seconds, thus associating Lanyon also with sexual desire. Lanyon is later to reprimand Jekyll for his behaviour, but Jekyll's response is to charge Lanyon with having the same desires inside him - as the earlier shot suggested. An example of the split-screen is when Jekyll's fiancee, Muriel (Rose Hobart), is shown alongside Ivy (the dancing girl) - one refined and respectable, the other licentious and immoral - two sides of the same character.

An example of the split-screen is when Jekyll's fiancee, Muriel (Rose Hobart), is shown alongside Ivy (the dancing girl) - one refined and respectable, the other licentious and immoral - two sides of the same character.One of my favourite instances of the point-of-view shot was in the final scene,

when Lanyon points directly into the camera as he accuses Jekyll. It's quite an unnerving effect, and cements the charge that the evil resident in Mr Hyde is resident in all of us.

when Lanyon points directly into the camera as he accuses Jekyll. It's quite an unnerving effect, and cements the charge that the evil resident in Mr Hyde is resident in all of us.March became the first actor to win an Oscar for a horror performance. Looking back, it is hard to deny he is pretty hammy in the role at times. Occasionally t

his works brilliantly - Jekyll's agony as he wrestles with his evil deeds and begs for God's forgiveness comes off effectively - but at other times, such as in the transformation scenes, it raises a few unintended laughs. The make-up, which becomes uglier as the film goes on, is generally effective, and is complemented by March's performance. By the end of the film, his movements are positively ape-like, as he swings furiously from the shelves of his laboratory.

his works brilliantly - Jekyll's agony as he wrestles with his evil deeds and begs for God's forgiveness comes off effectively - but at other times, such as in the transformation scenes, it raises a few unintended laughs. The make-up, which becomes uglier as the film goes on, is generally effective, and is complemented by March's performance. By the end of the film, his movements are positively ape-like, as he swings furiously from the shelves of his laboratory.Hopkins is oustanding as Ivy, the role taken by Ingrid Bergman in the remake. Her scenes with Hyde elicit

genuine terror, and her strong performance nicely makes up for Hobart's dullness as the fiancee.

genuine terror, and her strong performance nicely makes up for Hobart's dullness as the fiancee.I have yet to watch the film again with Greg Mank's commentary, which no doubt will enhance my appreciation of the film. I shall also revisit the 1941 version, which makes up in lush visuals and atmosphere what it lacks in sophistication.

My rating (1931): * * * * *

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home